The Ultimate Guide to Shutter Speed

+ FREE Shutter Speed Video Series

You can’t deny it – your photos haven’t turned out the way you want.

All you see is blur every time you try to capture an image of your kids playing.

Your motion shots never turn out crisp – they look soft and fuzzy. You just can’t figure out how other photographers perfectly capture fast moving objects all the time.

And it’s not just not being able to freeze motion that has you puzzled.

You’ve also seen soft, dreamy photos of waterfalls that look like cotton candy. But for the life of you, you can’t figure out how to get that effect in your own images.

Night photography? Forget it. Your photos keep turn out a black with little detail.

Well, it doesn’t have to be this way.

I’m David Molnar, and I’ve got great news for you.

All of these issues are related to the shutter speed of your camera – and I can help you finally get those crisp action shots you want. I’ll also cover how to show motion in your photographs of waterfalls, fireworks and light trails.

We’re about to dive deep into how to use shutter speed creatively.

By the end of this article, you’ll have complete confidence that you can correctly set the shutter speed on your camera to capture the effects you want.

But first, let’s start at the beginning: how does your camera’s shutter work?

Table of Contents

CHAPTER 1

How the Shutter Works on Your DSLR

When you press the shutter button on your camera, it starts a chain of events that captures an image.

Your DSLR camera has a digital sensor inside that records your image. (It works just like film did in older cameras.}

The DSLR also has a mirror. This mirror reflects the light coming in through the lens of your camera up to the viewfinder so you can preview the image that you’re about to take.

When you press the shutter button, the mirror comes up out of the way of the sensor.

Next, the shutter curtain opens up so light directly hits the sensor, capturing your image.

After the length of time has passed you set the shutter curtain to be open for, it closes so the light that was coming into the sensor is blocked.

Then the mirror comes back down – and the exposure is completed.

How the Shutter Works on a Mirrorless Camera

The shutter works a bit differently on a mirrorless camera like a Sony A6000 or a Fujifilm X-T100.

The main difference is that there is no mirror to come up when the shutter is pressed.

The light coming in from the lens travels directly to the sensor of the camera. Then the sensor transfers digital information directly to an LED screen or an electronic viewfinder so you can preview your image.

The shutter curtain still works the same way – it opens at the beginning of the exposure and closes when the predetermined time to expose the sensor is over.

Now that you know how the shutter on your camera works, here’s how you can manipulate shutter speed to create more impactful photos.

How to Create Emotion Packed Photos

DSLRs and mirrorless cameras have a setting that determines the speed in which the shutter opens and closes. How you adjust this setting creates dramatically different effects in your images.

Fast shutter speeds allow you to freeze motion in fast moving subjects. Typically used in wildlife and sports photography, fast shutter speeds drop you right into the heart of the action.

On the other hand, slow shutter speeds allow motion to show in your images.

If you’ve seen photos of moving water that look soft, or an image where you can see trails from tail-lights at night, or star trails in night photography, those images were captured with a slow shutter speed.

Here are some examples from my students:

So as you can see from my students’ examples, varying your shutter speed displays creates emotion and drama in your images.

Frozen motion in a photo creates excitement, and puts you in the middle of the scene. Allowing motion in a long exposure produces beautiful artistic effects in your photos.

Now, to fully understand how varying your shutter speed can produce these effects, let’s go over what “exposure” means.

CHAPTER 2

Exposure and Shutter Speed

Shutter speed is one of three factors that determine exposure, along with ISO and aperture. Together these factors are referred to as the ‘Exposure Triangle.”

The thing to remember about exposure is that you can’t increase one of these three factors without it affecting the other exposure factors.

For example, if you increase shutter speed, it allows less time for light to hit the camera sensor. (Because the shutter curtain opens and closes faster.)

To compensate, you’d need to shoot at a lower f-stop number. This increases the size of the aperture hole in your lens, which then allows more light to enter the sensor.

Your other option to allow more light to enter the sensor is to increase the ISO, which makes the camera’s sensor more sensitive to light.

But it increasing ISO can also introduce noise into the photo. You should always aim to shoot at the lowest ISO settings you can get away with because of this.

Let me give you an example of how these elements of the exposure triangle work together.

A Glass of Water is All You Need to Understand Exposure

For this example, let's pretend we are going to fill a glass with tap water.

One thing remains constant as we fill the glass – the size of the glass. So that’s how we can imagine ISO in this example.

Now to fill that glass, we can turn the tap wide open to fill it up fast. That’s like having a big hole in the aperture of your lens (smaller f-stop number).

Or we can turn the tap so it just lets out one drip at a time. The glass fills up slowly but surely. That’s like having a small hole in the aperture of your lens (bigger f-stop number.)

In either case, the glass gets filled. The only difference is how fast glass gets filled.

To extend the analogy, you can get a correct exposure by letting the light hit the sensor of your camera fast or slow – it doesn’t really matter.

Having an underexposed image is like turning off the tap when it’s only half-full. In other words, there wasn’t enough time for enough light to hit the sensor and record the image properly.

An overexposed image is like leaving the tap on until it overflows over the top of the glass. Too much light reaches the sensor and “blows out” some or all of the details in the image.

So setting your shutter speed correctly for your conditions makes sure that just the right amount of light hits the sensor for a correct exposure (like turning off the tap when the glass is full. )

If you want to learn more about how aperture (f-stop settings) affects your images, check out my aperture guide.

What is a Correct Exposure?

You hear photographers talk all the time about “correct exposure.”

Exposure really refers to the brightness of an image.

And here’s what you need to know about correct exposure – it’s completely subjective. It depends on the tastes of the photographer and the emotion they want to convey in the photograph.

You can slightly underexpose an image to make it appear dark and brooding, or slightly overexpose it to feel light and airy. In both cases, these exposures are correct. Why?

Because in both cases these choices let the photographer express what they felt when they pressed the shutter.

Check out this photo that was taken seconds apart from each other.

So how does this relate to shutter speed?

Shutter speed controls the brightness of an image. A slower shutter speed lets more light hit the camera sensor (and also allows motion to show in our images.)

A fast shutter speed lets less light hit the sensor, and lets us freeze motion.

By now you might be wondering which camera settings indicate fast shutter speeds and which indicate slow shutter speeds? Let’s look at that next.

CHAPTER 3

Shutter Speed Math Made Easy

When you look at the shutter speed dial on your camera, you’ll see all kinds of fractions like these:

1/60. 1/100. 1/250. 1/500. 1/1000. 1/2000.

When you see numbers like 1/60 and 1/1000, you might get a little confused over which shutter speed is faster.

It’s actually easy to figure this out. You can completely ignore the top number of the fraction.

Let’s think about the bottom number of the fraction as the speed of a car.

The Fast Car Guide to Shutter Speeds

What’s faster – a car going 60 mph or one going 1000 mph? Obviously, the 1000 mph car is going faster than the car going 60 mph.

You can think of shutter speed exactly the same way. A shutter speed of 1/1000 is much faster than a shutter speed of 1/60.

So what exactly does a shutter speed of 1/1000 or 1/60 mean? Well, shutter speed is expressed in hundredths or thousandths of a second.

A shutter speed of 1/1000 means it takes one-thousandth of a second for the shutter to open and close. A shutter speed of 1/60 of means the shutter opens and closes in one-sixtieth of a second.

Note: Some camera manufacturers don’t use fractions. They use numbers like 1000 but it means exactly the same thing as 1/1000 – the shutter opens and closes in 1/1000 of a second.

Shutter Speed Variation Examples

A longer (or slow) shutter speed allows motion to show in your photos because light hits the sensor for a longer period of time. It also creates beautiful motion blur.

Check out this example from my students:

In contrast, a fast shutter speed allows you to freeze motion because there is less time for the shutter curtain to be open. There simply isn’t enough time to show a motion in the photo.

Here is an example by one of my students:

But sometimes, your photos show motion when you weren’t expecting it. Here’s what’s likely happening.

Camera Shake - It’s Not a New Dance Craze...

While motion blur can look really gorgeous, it’s not so great when you want a clear, crisp photo.

The disappointing blur isn’t caused by your photo being out-of-focus.

More likely, the unwanted blur is caused by the photographer’s nemesis – camera shake.

Remember when I said that a slower shutter speed allows motion to show in a photo? Well, we all shake a bit without knowing it. And when we shoot at slow shutter speeds that shaking motion shows up in our photos.

This blur is what’s known as camera shake – and typically it happens when we try to shoot handheld at shutter speeds slower than 1/60 of a second.

A few photographers can get away with shooting at shutter speeds slower than 1/60 – but they are exceptions.

They use tricks like holding their breath and bracing themselves against a wall to control shake as the press the shutter button.

But the majority of us can’t handhold at shutter speeds slower than 1/60 and avoid camera shake. So, if you want to drop your shutter speed below 1/60, put your camera on a tripod.

Here’s something else you need to consider when deciding if you need to set up your camera on a tripod – the focal length of your lens.

CHAPTER 4

One Over/Reciprocal Rule:

Keep Your Images Crisp

The focal length of your lens also affects how long you can hold steady during your shot.

The longer your lens is, the more it increases your risk of camera shake. (Longer lenses are heavier and this makes them more difficult to hold them steady.)

What does minimum shutter speed mean in photography?

So here’s a handy rule to prevent camera shake. It’s called the ‘one over’ or reciprocal rule. And it’s very simple.

Don’t shoot at a shutter speed less than the focal length of your lens.

For example:

100 mm lens = not slower than 1/100

200 mm lens = not slower than 1/200

80 mm lens = not slower than 1/80

What if you have a 50mm or 35mm lens? Then we go back to the rule where we don’t shoot handheld at speeds below 1/60.

Check out this handy guide below!

Whoa! We’ve covered a lot in this chapter.

After a while, knowing which shutter speeds to use to freeze motion or show motion in your photos becomes second nature.

But to help you out until that happens, I’ve put together a cheat sheet to help you select the right shutter speed when you’re on a shoot.

Grab Your Shutter Speed Cheat Sheet

Download this shutter speed cheat sheet and tuck it in your camera bag so you can refer back to it whenever you need.

Still feel unsure about how to adjust your ISO and aperture to in order to achieve the shutter speeds shown in the cheat sheet?

I’m going to walk you through how to use a semi-automatic camera mode that sets the ISO and aperture for you – shutter priority.

CHAPTER 5

Shutter Priority on Canon, Nikon and Sony Cameras

Shutter priority mode is a perfect setting for learning how to use shutter speed creatively. In this mode, you just need to set the shutter speed. The camera automatically adjusts the ISO and aperture setting for you.

Shutter priority mode is perfect for new photographers to play with shutter speed because it allows you to focus on composition without the need to be constantly adjusting your settings.

How to Switch Your Camera into Shutter Priority Mode

Each camera manufacturer has the shutter priority mode located in a different spot. I’ll walk Canon, NIkon and Sony users through how to change into this semi-automatic mode.

But before we do this, make sure your camera is set to Auto ISO – regardless of your make of camera. If you’re unsure how to do this, refer to the owner’s manual for your camera.

How to Change to Shutter Priority on Canon

Canon calls shutter priority mode by a different name – time value. (It’s indicated on the dial as Tv.) It is exactly the same as shutter priority on a Nikon or Sony.

Look on top of your camera. Turn the dial and line up Tv with the white mark on the left side of the dial.

Here’s an illustration: We should have an arrow pointing to Tv here.

Next, check the display on your camera.

Once you’re into the shutter speed adjustment portion of the screen, turn the dial on your camera until you’ve set your desired shutter speed.

How to Change to Shutter Priority on Nikon

The dial for Nikon entry cameras like the D3400 are located on the top of the camera as well.

Just like with the Canon, there is a white line located to the left of the dial. Turn the dial and line up the “S” (for shutter priority) with the white mark.

Next, look on the back of your camera and press the “i” button.

Next, turn the dial located on the top right of your camera until you get your desired shutter speed.

How to Change to Shutter Priority on Sony

Like Nikon, Sony indicates shutter priority mode with an “S.” Line the S on the dial up with the white mark to the left of the dial.

Next, turn the dial located on the top right of your camera until you get your desired shutter speed.

Easy peasy! And now let’s talk about how shutter speed works to make your photos more creative.

CHAPTER 6

Working with Shutter Speed

Back in Chapter 3, I talked about how you can either allow motion in your images with a slower shutter or freeze it with a fast shutter speed.

I’m going to show you exactly what I mean with a little demo I shot with a running fan.

When I shot a photo of the fan at 1/60, the blades of the fan aren’t distinct. All you see is the blur of the blades in motion.

I increased the shutter speed to 1/200 in the next photo. While you can start to see a difference, there is still a lot of motion blur.

Bumping up the shutter speed to 1/500, you can begin to see the outline of the individual fan blades but the image still isn’t crisp.

Increasing the shutter speed to 1/500 shows a lot more detail, but the image could be crisper yet.

Now at 1/1000 you can see the individual fan blades in detail.

Now that you have a good idea of how varying shutter speeds can show or freeze motion, let’s discuss the creative effects you can get from a long exposure.

CHAPTER 7

Creative Effects with Slow Shutter Speeds

As we discussed in the last chapter, fast shutter speeds freeze motion; slow shutter speeds show motion in your images.

You saw it for yourself in the fan demonstration.

But sometimes, just because your image is technically correctly exposed doesn’t mean it conveys the emotion you want your viewer to feel.

That’s why this chapter is all about slowing down your shutter speed to capture motion. The effect is stunning when done correctly.

When to Use a Slow Shutter Speed

Use a slower shutter speed whenever you want to capture motion in your subject.

(Deliberately slowing down your shutter speed to capture more motion and light is also called long exposure.)

Long exposures are ideal for low light conditions since a slower shutter speed allows your camera sensor extra time to record light.

Let’s look at some ideal situations for taking long exposures.

- Night sky photography – long exposures are allow photographers capture the Milky Way and star trails. Leaving the shutter open for a longer period of time longer allows more light to enter the sensor under low-light conditions.

- Fireworks – a slow shutter speed shows the motion of the fireworks as they fall in the sky.

- Cityscapes at night – choosing a long exposure at night shows the movement of cars and vehicles in the city with trails of light

- Flowing water and waterfalls – slowing down your shutter speed allows you to capture the movement in the water. A long exposure makes flowing water look soft like cotton candy.

Now that I’ve shown you some examples of allowing motion in your photos, I’ll walk you through how to capture this effect in your own photos.

Tutorial: How to Capture Motion in Flowing Water

Ever see those dreamy photos of soft-looking flowing water? These photos are long exposures captured with slow shutter speeds.

Let me walk you through how to get that effect in your own photos.

To capture the motion of the water, we’ll be shooting with shutter speeds slower than /60. This means that your camera needs to be mounted on a tripod to avoid camera shake.

Set your camera to AUTO ISO (so you don’t have to worry about the brightness of the image.)

Now begin to decrease your shutter speed. Start with 1/30 second; check if the image is showing motion.

If not, decrease the shutter speed down to 1/15 – check again for motion in the image.

If you’re still not seeing the effect you want, decrease your shutter speed down to ⅙.

You can try to keep decreasing shutter speed, but eventually the image will become too bright (overexposed.)

Why? Everytime you decrease the shutter speed, it allows light to hit the camera sensor for a longer period of time.

Keep experimenting with decreasing and increasing shutter speed until you get the effect you want.

Again, ISO and aperture settings are controlled by the camera in Shutter Priority mode, so all you need to do is keep changing up the shutter speed and checking your images.

Speaking of checking your images, here’s a simple test to nail the right shutter speed for action photos.

CHAPTER 8

The Lightroom Test for Crisp Images

Even if you think you’ve successfully frozen motion in your photo, there is one way to tell for sure.

Sometimes you think you’ve nailed freezing motion but on closer inspection, you can still see a bit of motion blur. Here’s how to tell if your images are really crisp.

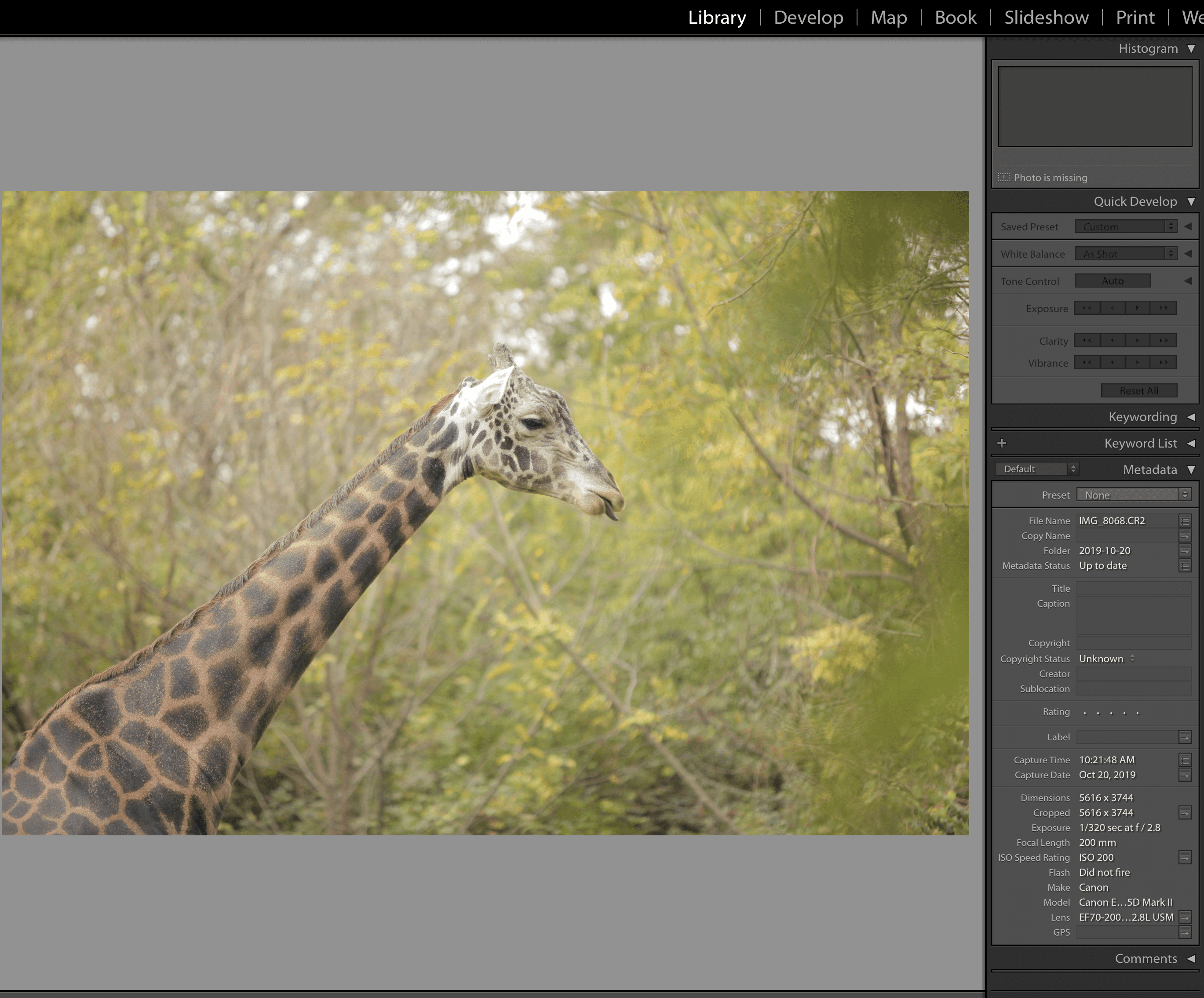

Import your images into Lightroom and zoom in. If you still see some blur, it means the shutter speed you selected wasn’t quite fast enough to freeze motion.

How can you tell what shutter speed you used to capture the image? Import your photos into Lightroom and you’ll see a wealth of information displayed in the image EXIF file.

The EXIF provides information about the make of camera used to capture the image, the focal length of the lens, and the aperture, shutter speed and ISO settings used to capture the image.

After you’ve imported your images into Lightroom, zoom in on all of your photos. Note which images look crisp – and which ones look a little soft. Check the EXIF to discover which shutter speeds produced the crisp images.

Next, note these shutter speeds as a starting point the next time you take an action shot. (Hint: keep a small notebook in your camera bag to refer to whenever you need to check your settings.)

Suggested Shutter Speeds to Freeze Motion

Here are a few suggested shutter speeds to freeze motion in your subjects. These suggestions are just guidelines. Feel free to use them as a starting point to experiment with freezing motion in your images.

- Kids at play – if you’re a parent, I don’t have to tell you that kids are fast! If you want to capture your kids at play, try shooting at 1/250. (Or even faster if you have especially speedy kids!)

- Sports/action/wildlife photography – if you want to capture a runner in full stride, athletes in a team sport or wildlife, try shooting at shutter speeds from 1/500 to 1/800. If you’re still seeing motion in your photos (they don’t look crisp) bump up your shutter speed even higher.

- Birds/cars on a track – to freeze motion in images of birds or cars on a racetrack you need a very fast shutter speed. Try a shutter speed of 1/1000 to 1/2000 for these subjects.

Remember, these are only suggestions. Experiment to find the perfect shutter speed for your shooting conditions.

Next up: let’s answer some questions about how lenses affect shutter speed.

CHAPTER 9

How Does Your Lens Affect Shutter Speed?

Earlier in this article, we talked about the One Over or Reciprocal rule about the slowest shutter speed you can shoot at handheld.

That rule applies if you’re shooting with a prime lens. (A prime lens is a lens with a fixed focal length – for example a 50mm lens.)

But what about shooting with a zoom lens that has multiple focal lengths? Glad you asked.

Zoom Lenses and the One Over Rule

The one over rule still works with zoom lenses. Just consider the focal length you’re shooting at.

Example: if your lens is zoomed out to 100mm, don’t shoot at a speed lower than 1/100.

Again, don’t shoot handheld at speeds below 1/60 no matter what the focal length of your lens is.

Example: 1/60 is as low as you can go handheld with a 50mm lens.

If you want to shoot at shutter speeds lower than the focal length of your lens (maybe you want to shoot fireworks or a waterfall) put that camera on a tripod.

Also consider that the longer your lenses are, the heavier they are. With these lenses you could experience camera shake even if you follow the 1/60 rule for handheld shooting.

Crop Sensor Cameras - Exceptions to the One Over Rule

The ‘One Over’ rule works perfectly for full frame cameras. But what about crop sensor cameras like the Canon Rebel series or the Nikon DX series?

As you might expect, a crop sensor camera has a smaller sensor than a full frame camera does.

Crop sensor cameras capture a tighter field of view than a full frame camera does shooting from the same distance, with the same f-stop and focal length.

At the same time, cropping the edges of the image effectively increases the focal length of the lens.

Typically, a crop sensor produces a magnification effect of around 1.5 – 1.6x.

So does that mean that we should take the magnification effect of a crop sensor into account when determining if we can shoot handheld?

Yes! For example, a 50mm lens on a crop sensor acts like a 75mm on lens on a full frame camera because of the magnification factor. So we could shoot safely shoot handheld at shutter speeds of 1/75 or above with this camera and lens without introducing camera shake.

Note: some pros prefer crop sensors in certain situations because it allows them to get greater focal length out of a smaller and lighter lens.

That’s important when you’re lugging around a camera all day!

Now that we’ve covered the difference between crop sensor and full frame lenses when it comes to shooting handheld, it’s time to discuss the limitations of kit lenses.

Kit Lens Limitations

Many Nikon and Canon entry level cameras come with small zoom lenses (typically 18-55mm.)

The big drawback to these kit lenses is that their maximum aperture setting is f3.5 – f5.6.

This limitation affects your ability to freeze motion in low light conditions – and to shoot long exposures as well. The reason is often these apertures aren’t large enough to let in enough light in these conditions.

The solution? Purchase a f2.8, 50mm prime lens.

The larger aperture on this lens allows the aperture to open wider and thus create crisper photos. (Note: any lens that has a maximum aperture of f2.8 or less is known as a fast lens.)

Fast lenses are far superior to kit lenses for night photography, indoor-low light conditions and shooting action shots.

A 50mm prime lens is also inexpensive as far as lenses go. They typically go for $200 and below. Just make sure you purchase one that fits your camera make and model.

A discussion on how lenses affect shutter speed wouldn’t be complete without mentioning image stabilization.

Image Stabilization and Shooting Handheld

Certain Canon and Nikon lenses have a feature to help reduce camera shake called image stabilization (Note: Nikon calls this feature Vibration Reduction.) Sony also has its own version of image stabilization, but it is built into the camera body instead of the lens.

Image stabilized lenses contain floating elements that work to counter shaking hands. When image stabilization is activated it allows you to shoot handheld at speeds from 2-4.5 slower than is possible handheld.

But having an image stabilized lens doesn’t mean at some point camera shake won’t be introduced. It just gives you a little extra leeway.

Something to remember is that you should turn image stabilization off if you’re shooting on a tripod.

When your camera is on a tripod, the image stabilization system will detect its own vibrations, and move in response – introducing the camera shake you were trying to avoid!

Our last chapter is an advanced lesson on shutter speed and flash photography. Pay close attention to this section. If your shutter speed is too fast when you’re shooting with a flash, your photos could end up with big, black lines through them!

CHAPTER 10

Mixing Flash with Ambient Light

Before we go any further, let’s define what ambient light is.

Simply put, ambient light is the available light in a shooting situation. Ambient light comes from two sources:

- Sunlight, or indoor lighting

- Flash, which is supplemental light

Naturally the amount of available light affects maximum shutter speeds. Shutter speed does not affect how much of the flash hits your subject (it does not change the exposure on your subject’s face.)

What Do You Need to Know About Shutter Speed and Flash?

The most important thing to know when you’re shooting with a flash is something called maximum sync speed. This is the shutter speed that your flash and camera can sync up.

Most cameras have a maximum sync speed of 1/200.

If you see the dreaded black line in the photos you shot with a flash, it means that you shot at a speed faster than the flash could keep up with the camera. (The shutter opened and closed before the flash could fully fire.) The black line you see is part of the shutter captured in your photo.

Creative Use of Flash and Shutter Speed

When the flash fires, it freezes the subject. But you can create more creative images

by leaving the shutter open long enough to capture background motion.

Background motion brings the excitement of an event into your image – it’s ideal to try this at a wedding or live event.

You can also use flash to darken the sky during the day (yes, really!)

Light Painting

You need a pitch black room and a camera on a tripod for this one. You should also have a remote trigger and a flashlight. Set your camera for a long exposure, say 30 seconds. (Note – this shutter speed will appear in your settings as 30”, not as 1/30.)

One the flash triggers, your subject can move out of the frame. Now, point your light source right at the camera and make some cool designs in the air. You’ll see the trails of lights in the and the subject both captured in your image.

Create Night During the Day

Shoot with a flash at maximum sync speed to make the sky darker in the middle of the day for a moody effect. (The flash freezes the subject and reduces the amount of ambient light that appears in the image.)

Wow, we’ve finally come to the end of this article. I hope you learned a lot!

If you’d like to learn more about shutter speed and aperture, I invite you to come to my FREE webinar workshop called “Show Your Camera Who’s Boss.”

You’ll discover:

- The three factors that give you a perfect photo – every time!

- What the different shooting modes are on your camera (and how you can use them to get the BEST results in your photos)

- The confidence to finally get your camera off full AUTO mode – guaranteed!

PLUS – You’ll receive some valuable photography cheat sheets as my gift for attending!

How to join me on the workshop? Just click the button below to reserve your spot.

CHAPTER 11

FAQ's

Got questions? I've listed out some of the most common questions below that I get about shutter speed.

Q. What is the shutter and how does it work on my camera?

When you press the shutter button on a DSLR, it sets a chain of events in motion. DSLRs contain a mirror that reflects light from the lens up to the viewfinder. When the shutter is pressed, the mirror comes up out of the way of the camera sensor. Next, the shutter (which is a two part curtain) opens and exposes the sensor to light. When the exposure is complete, the sensor curtain closes, and the mirror comes back up into place.

Q. What is shutter speed and how does it affect exposure?

Shutter speed is the amount of time it takes the shutter curtain to open and expose light to the camera sensor, and then close and block off light to the sensor again. The length of time the shutter stays open really doesn’t matter as long as the sensor can capture enough light to properly expose the subject.

Q. I’m not sure what the shutter speed fraction numbers mean?

Shutter speed is measured in thousandths and hundredths of seconds. So 1/1000 means that the shutter opens and closes in 1/1000 of a second. 1/60 means the shutter opens and closes in 1/60 of a second.

Q. How do I tell which numbers indicate fast shutter speeds and which indicate slow shutter speeds?

It’s actually quite easy. Ignore the top numbers of the fractions and think of the bottom number in terms of speed. Is a car going 60 mph faster or slower than a car travelling 1000 mph? The car going 1000 mph is much faster than the one doing 60 mph. So a shutter speed of 1/1000 is much faster than 1/60. (Some camera manufacturers don’t use fractions, they use whole numbers like 60, 100, 200, 500, 1000 etc. )

When shutter speed slows to less than one second, you won’t see fractions any more. You’ll see these numbers with a hash, like 1”, 1.3”, 1.6”, 2” etc. For example when you see 1”, it means that the shutter will take 1 full second to open and close.

Q. What is a correct exposure?

It’s any exposure that conveys what the photographer felt when they pressed the shutter button. They might make a creative decision to slightly underexpose an image for a dark and brooding effect, or slightly overexpose it for a light and airy effect.

Q. Why would you want to vary your shutter speed?

Because varying your shutter speed helps you convey emotion. It allows the photographer to show motion in the photo or freeze it for a different feeling.

A slow shutter speed allows you to show motion in your photos (for example, in flowing water.) It also allows you to capture better images in low-light conditions.

A fast shutter speed freezes motion. It’s ideal for sports and action shots.

Q. How do I know what shutter speed to shoot at when I want to show or freeze motion?

Here are some suggestions depending on your shooting conditions.

Q. Is there a guideline for minimum shutter speed when you shoot handheld?

Yes! Don’t shoot handheld at shutter speeds slower than 1/60. Of course, you can shoot at shutter speed slower than this if you use a tripod.

Q. If I have Image Stabilization turned on can I shoot handheld slower than 1/60?

You can probably shoot a little bit slower, but not a lot. Everyone shakes to some degree. If you’re shooting with a longer heavier lens, you might even start to get camera shake at speeds about 1/60.

If you’re shooting on a tripod, turn Image Stabilization (aka Vibration Reduction) off.

Leaving it turned on when your camera is on a tripod can introduce camera shake.

Q. What is the One Over or Reciprocal Rule?

The One Over rule refers to shutter speed and the focal length of your lens. For example, if you’re shooting with a 100mm lens, your shutter speed should be no slower than 1/100 handheld. If you’re shooting with a 200mm lens, the minimum shutter speed should be no less than 1/200. But, no matter what the focal length of your lens is, don’t shoot below 1/60 handheld.

Q. Does shooting with a zoom lens affect the One Over Rule?

Not really. Just check what focal length you’re zoomed out to, and match the shutter speed to that focal length. For example, if you’re zoomed out to 200mm, your minimum handheld shutter speed should be no less than 1/200.

Q. Does shooting with a crop sensor camera affect the One Over rule?

Yes, because a crop sensor provides a magnification factor of about 1.5 times the focal length of your lens. So a 50mm lens on a crop sensor camera acts like a 75mm lens on a full frame camera. So your minimum shutter speed should be no slower than 1/75 unless you use a tripod.

Q. Is there a maximum shutter speed I should use with a flash?

Most cameras can’t sync with a flash at shutter speeds faster than 1/200. If you try to shoot faster than this, the flash can’t keep up. You’ll see a black line through your photos, which is part of the shutter captured in your image.

Q. How can I use shutter speed creatively with flash?

We covered how to light paint and darken skies using shutter speed and flash in this section [link]

Heads up — we’re making things better.

We’re currently migrating members to our new platform.

Thanks for your patience — everything will be back shortly.